exhibition

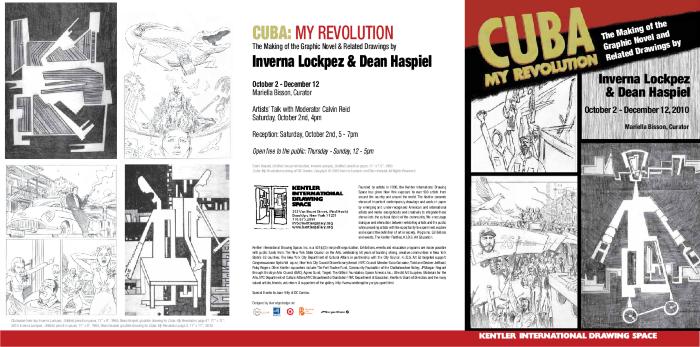

Dean Haspiel and Inverna Lockpez, Cuba: My Revolution; The Making of the Graphic Novel and Related Drawings

Date

October 2 – December 12, 2010Opening Reception

October 2, 2010Curated By

Mariella BissonArtists

Deal Haspiel, Inverna Lockpezexhibition Images

Click to Enlarge.

Press and Promotion

About the exhibition

Collaborative exhibition by artists Dean Haspiel and Inverna Lockpez

Artists' Talk: October 2, moderated by Calvin Reid

Cuba, Comics and the Revolution That Failed: The Life of Inverna Lockpez

In a volume that could easily be compared to the essays in the classic anti-Communist anthology The God That Failed, cartoonist Dean Haspiel has collaborated with Inverna Lockpez to create Cuba: My Revolution, a new graphic work that transforms her true life story into a fictionalized account of her extraordinary journey from idealism and political illusion to political freedom, political reality and a hard-won self-realization. While the book is presented as fiction and names have been changed throughout, the story on which it is based is true and vividly realized, and will very likely take its place among other harrowing personal accounts of brutal disillusionment with the Cuban revolution.

Originally published in 1949, The God That Failed offered the personal stories of such 20th-century literary giants as Arthur Koestler and Richard Wright and their own circuitous routes from being political acolytes to eventually having a grasp on the monstrous nature of the Communist regimes they once had admired. Lockpez’s account is much the same, and thanks to the drawings of Haspiel and the book’s strategic use of limited color—the vivid and allegorical use of red throughout by the acclaimed colorist José Villarrubia—the story she tells in Cuba: My Revolution is brought brilliantly to life in a visual re-creation of her hopes, imprisonment, repression and disappointment as well as her eventual escape to America and freedom.

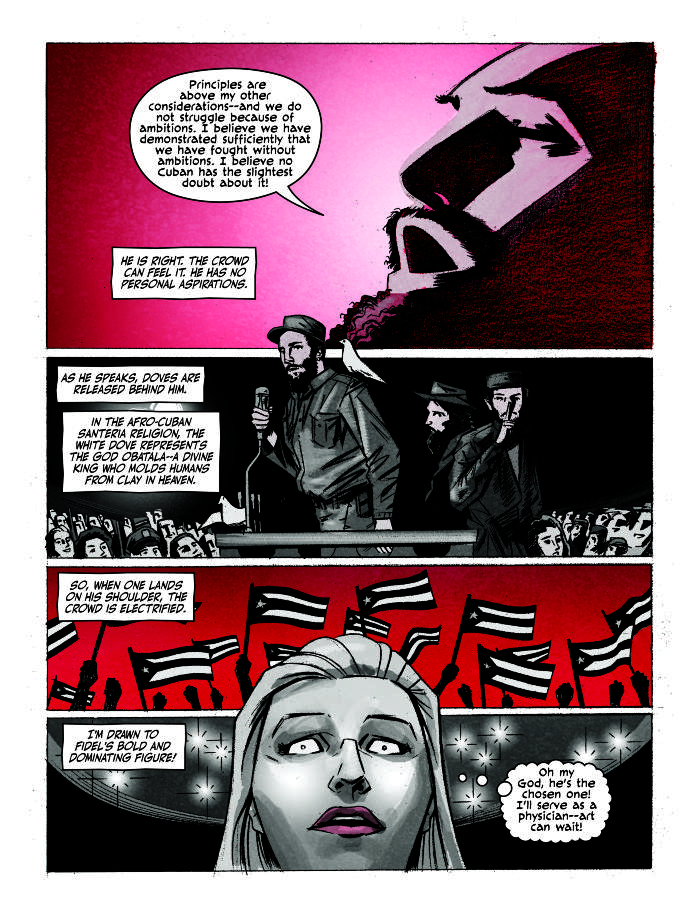

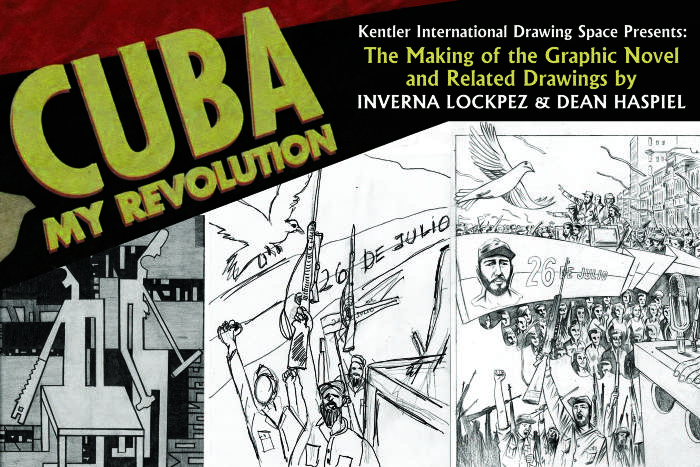

In the book, the full chromatic range of red serves as both an integral part of the narrative and a powerful symbolic aura that plays across Haspiel’s rich and kinetic gray-scale drawings. More than simply a color, red becomes an emotional veil that tints and enriches our perception of the action on the page. Red is, of course, the color of the Communist Party; but it is also the color of blood and suffering and of passion and commitment . Throughout the book its use underscores the varying ways in which red figures in the lives of the characters and in the broader fate of the Cuban people—from the bloody battlefields of the Bay of Pigs to the propagandistic self-deification of Fidel Castro to the horrific scenes of torture and degradation suffered by the protagonist at the hands of the regime.

Cuba: My Revolution begins in Cuba in December 1958, as the central figure, 17-year-old Sonya--dressed in a brilliant red dress for an evening out—defends Castro to her step-father, a supporter of the American puppet, Batista. Haspiel’s drawings work to both denote the action and to put the characters in context. In a scene that depicts Sonya’s arrival at a fashionable nightclub with her mother and an escort (Silvio, a would-be but undesired admirer of Sonya). The panels depicting the nightclub scene are placed over a deep burgundy tinted image of Castro’s guerrillas marching through the Cuban jungle. Later, as Castro marches triumphantly into Havana, an infatuated Sonya recounts how he “has no personal aspirations,” her words set over a blockish yet ethereal illustration of Castro that virtually glows in a field of low-key melon red radiating outward from his form through an eerie gradation from magenta to a heavy bloodred.

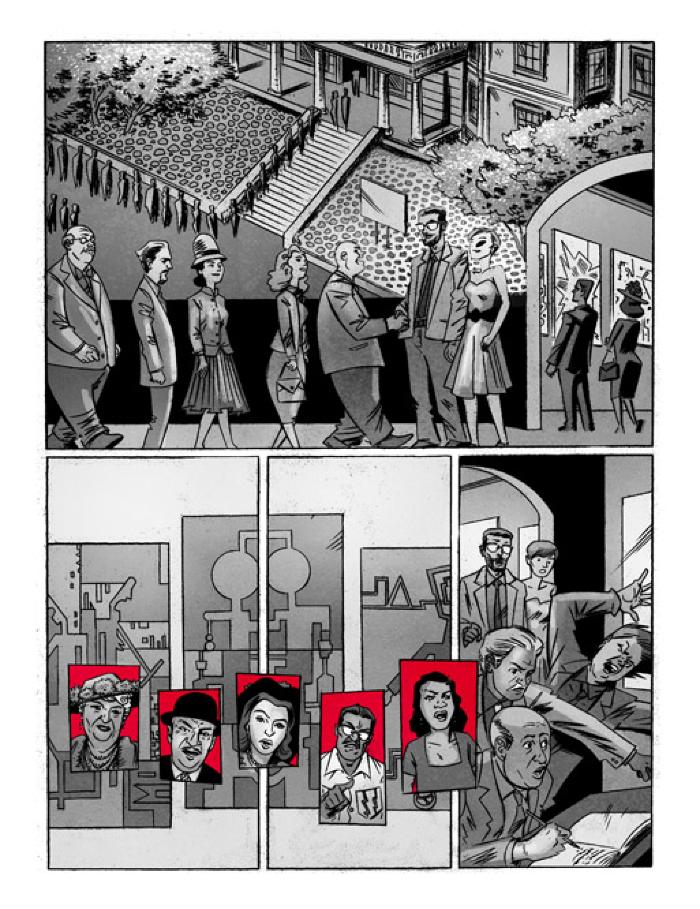

Sonya is an aspiring artist who had originally rejected medical school in favor of becoming a painter until, swept up in revolutionary fervor, she decides that “art can wait!” Later she will discover that any art other than social realism or hagiographic portraits of the leaders of the revolution is anathema to the Castro regime at that time. Indeed, I feel there is a certain irony involved in writing an essay that will accompany a gallery exhibition of Haspiel’s drawings for this graphic novel as well as the abstract drawings and other gallery works of Lockpez, who managed to achieve her dream of becoming an artist, a dream that for her and many others was brutally quashed in the years following the Cuban revolution. Cuba: My Revolution is both the story of how her dream was suppressed as well as a testament to both her talent and her determination to become an artist. As Sonya was about to learn, art was simply another avenue for political indoctrination. Imagination, invention and individual passion—the driving vectors of art—were immediately labeled counterrevolutionary and decadent, and Sonya would find out just how powerful a social indictment that could be in Castro’s Cuba.

Sonya forgoes art school to become a surgeon. Not even that sacrifice, however, is enough to satisfy a regime as much at war against its own people as it is in opposition to foreign intervention. When Sonya volunteers to be sent to Playa Giron (known as the Bay of Pigs to us) to provide medical treatment during the American-sponsored invasion, she is not only forced to confront the brutality of the regime but also finds its horrors turned upon herself. Her determination to provide medical treatment to a mortally wounded prisoner brings her under suspicion. Sonya is torn between reality and illusion, forced to examine her dreams of what the Cuban revolution was supposed to mean and the all too real nightmare of repression, torture and lies into which it had devolved.

Of course it took a talented collaborator to re-create the events, personalities and emotions embedded in Lockpez’s story. It almost seems as though Haspiel--a multiple Eisner and Ignatz nominee (two prestigious awards for comics creation)-- has been working to build his interpretive skills and narrative chops over the course of several previous works just to take on a story of this level of poignancy and political substance. His critically acclaimed graphic biographical collaborations with the late and much-praised autobiographical comics writer Harvey Pekar (The Quitter) and novelist Jonathan Ames (The Alcoholic) seem like ideal works for learning to navigate the depiction of eccentric memoir and the emotional and psychological infrastructure of an individual life. Haspiel’s well-known and hilarious character Billy Dogma—a shrewd crypto-libertarian romantic who speaks in a disjointed but inspirational lexicon of social liberation and self-help—and his girlfriend, Jane Legit, also provide an engaging and humorous platform for mastering both the contradictory details needed in the depiction of a life and the social infrastructure that supports and nurtures it—or turns it all to shit.

Haspiel managed to bring his experience translating the lives of Pekar and Ames into visual narrative to the difficult task of interpreting a version of Lockpez’s life story with balance and prosaic detail—portraying daily life in the Cuba of the time as we march inexorably from the American-backed oppression and social horrors of the Batista regime to the Soviet-driven totalitarianism and brutal political repression of Castro. Because Haspiel and Lockpez have been connected through family relationships since his childhood, he has heard her story, a bit at a time, over the course of many years. He was able to work with her to refine the narrative and to have access to a trove of photographic source material on which to base his depictions of the period. Lockpez’s story offers a rich and depressingly clear window on the nature of the Cuban political regime and its manipulation of the medical profession and other professional disciplines, as well as its destruction of a genuine Cuban art scene and that art scene’s replacement with a bureaucratic creative orthodoxy.

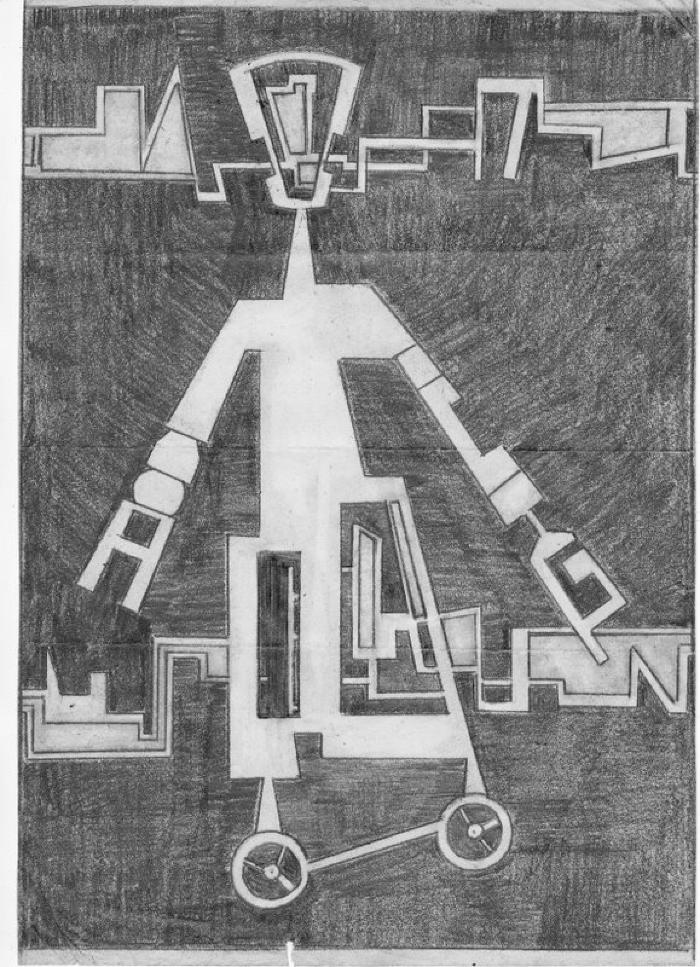

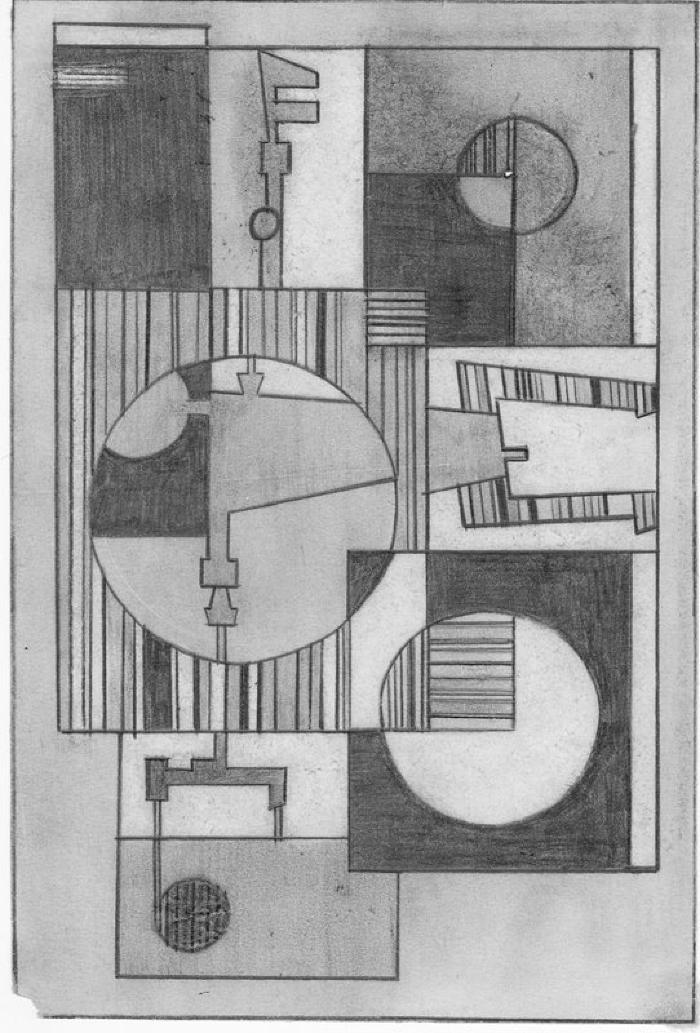

Curator Mariella Bisson chose to include a set of Lockpez’s drawings in this exhibition. They offer a fascinating and delightful coda on the raw experiences detailed in the graphic novel. Lockpez’s flat abstract pieces are indeed emblematic of certain works of the great Russian abstractionists like Kandinsky and Malevich, and they offer an ironic reflection on her work and on the overbearing role Russians would play in her life in Cuba. These small, intricate drawings hover in abstract space, crisply rendered and visually distinctive even as they suggest a sense of the physical body extending itself, forming tool-like extremities suggesting implements of work and vehicular motion. Indeed, strangely enough, some of the works even suggest the panels of a comic book.

This exhibition of the original comics pages of Cuba: My Revolutionalso includes pages that didn’t make it into the final work and other supplementary works. The show not only provides the viewer with a chance to see the process behind the graphic novel but also offers us a chance to contemplate the comics page as an original artwork. While comics pages are not necessarily intended to be seen as stand-alone gallery works, the care, craft and formal invention of creating them bring to bear all the expertise associated with the gallery artist. Indeed, comics may require a more extensive set of creative tools. They are an amalgam of prose and imagery-- something that is unique. In Cuba: My Revolution, Dean Haspiel and Inverna Lockpez have collaborated to create a work that highlights comics at their best—a bravura storytelling medium and a visual and contemplative feast for the eye and for the mind.

--Calvin Reid is a senior news editor at Publishers Weekly and is co-editor of PW Comics Week, PW’s weekly e-mail newsletter on graphic-novel and comics publishing.