The Good Fortune of Hurricane Katrina

It’s a simple coincidence, thousands of miles away from New Orleans, that forces Helen Rubinstein to understand the gravity of Hurricane Katrina.

09.05.11 published in The Bygone Bureau

I moved from New Orleans to New York in August of 2005, three weeks before Hurricane Katrina. “Moved” is maybe an unfair word — I had been away at college for most of the previous four years. But I’d spent that summer with my family in the house where I’d grown up, getting ready for the first big step of my adulthood: a one-way ticket to New York City, where I hoped to find a job and a life. I brought with me one suitcase of warm-weather clothes — enough to last a two-month sublet of a friend’s furnished room — and told myself that October was when I’d make my real decision about which city I wanted to call home. The winter clothes, the books and lamps and coats — these two months were preliminary, I told myself, a test; those heavier things could come later.

Part of New York’s allure was the personal history I had there: my mother grew up in Queens, her parents immigrants from Europe after the war. So when I woke up from a dream about my grandfather on one of those first Saturday mornings — August 20, to be exact — I decided I’d walk to see the building in Brooklyn where he’d once owned a general store.

My path from Park Slope to Red Hook that Saturday was as tentative as my relationship to the city, so it seems particularly miraculous that I arrived at 353 Van Brunt Street at the exact moment I did. I was scared by a boy bicycling past with a giant goiter on his neck, scared by a chorus of barking dogs that turned out to come from a doggie daycare, and disappointed enough to almost turn around when I saw that the building, now a gallery, was closed, its metal grate pulled down. But instead I called my mother to confirm the address, and lingered inside the café next door. And then I passed number 353 again. In front of the building where my grandfather’s store had been, a couple stood talking to a woman who was gardening behind a fence in the adjacent lot.

“Come in,” I heard her say. “I’ll show you around.” The couple on the sidewalk thanked her as she disappeared inside to open the front door.

“What’s going on?” I had to ask.

“Oh, my grandfather used to own this building,” said the woman on the sidewalk. “She’s going to give us a tour.”

“Your grandfather used to own this building?” I said. “My grandfather used to own this building.”

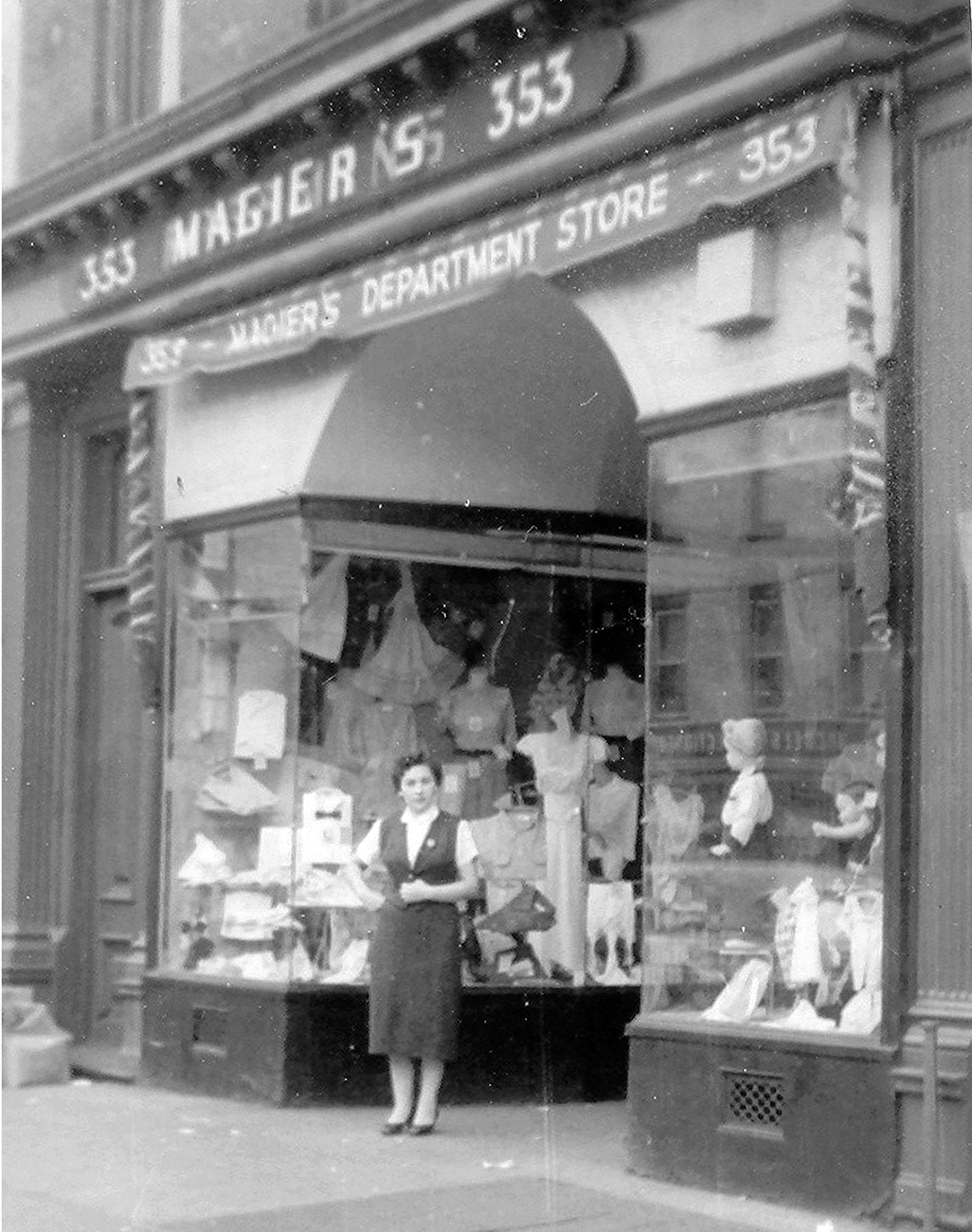

For a moment, we were confused. She asked me my last name and I hers; we double-checked the building number and street. Marjie’s grandfather, Charles Kentler, was the gallery’s namesake, she told me; she pointed to the cornice where his name was still inscribed. My grandfather’s name had once been on the building too, I told her; I’d seen it there — MAGIER’S, for Mendel Magier — in scores of old photos.

And then we realized that both of our grandfathers had owned the building — hers at the turn of the twentieth century, mine in the fifties and sixties. She and her husband had decided to stop by after driving into the city from Fairfield, Connecticut, for brunch that morning.

When Florence Neal, the building’s current owner, opened the front door, Marjie introduced me.

“This is Helen,” she said. “Her grandfather used to own the building, too.”

It was the kind of moment people like to call a New York moment — the kind of encounter that can happen only in a city as crowded with potential for coincidence as this one. Florence, who carefully restored the building after receiving it through the city’s artist housing program in 1987, also curates a collection of neighborhood photos and documents called the Red Hook History Files. She was the perfect person to have opened the door onto two granddaughters of two of the building’s unrelated past owners, and for the next few days, she and Marjie and I would email each other, partly to share stories and pictures, but also just to reassure ourselves that our meeting had really happened.

After I left the gallery that day, I wandered up the street and got lost in a labyrinth of art and wine at the waterfront artists’ summer show; later, when I went looking for the bus, the organizers of a block party begged me to accept a plate of fried fish and chocolate cake. It was a strange and magical day. Perhaps equally as memorable as my encounter with Florence and Marjie was when, after floating up Van Brunt Street in hazy disbelief, I found myself standing abruptly before the Statue of Liberty. It was my first glimpse of her since getting to New York, and I felt then that I’d truly arrived.

I was standing in the same spot the following Saturday, August 27, writing a postcard to my family, when my mother called and told me about the storm that was set to hit New Orleans around Monday. She was waiting in a miles-long line for gas; my sister, who’d just started her freshman year of high school, was home and worried that the math test she had scheduled for Tuesday would still take place even though school was projected to be closed on Monday. I mumbled something reassuring into the phone, then finished writing the postcard and put it in the mail.

That postcard did make it to my parents’ house, but not until late December. I was home then, helping with repairs, showering at a gym and eating from the mini-fridge my dad had hooked up in the least-damaged room upstairs. When I pulled the postcard from the mailbox it took me a minute to realize what it was, where and when and even from whom it had come.

“Look what finally arrived,” I said, carrying it into the house. To me, it was a relic of an enchanted time: enchanted because it was on the other side of Katrina, but also because it was so close to that first afternoon in Red Hook, when my presence at that exact place and time in New York City had seemed so auspiciously fated.

My mother read it over quickly, then put it in the trash. “It’s old,” she said when I asked her why — I’d never seen her throw away anything I’d mailed her before — but I think the date on that postcard offended her with its ignorance of all that was to come, its childish certainty that a hurricane scare would never be more than just that. When she saw that I was upset, she said, “It was automatic. I guess I’m just in the habit of throwing things away.”

“But it was from Red Hook.”

I knew how stupid it sounded. Not only was I fetishizing my associations with a neighborhood, like too many an overeager New Yorker, but I was whining about a postcard while standing in the dusty, gutted entrance to my family’s house, where there was no longer furniture, flooring, or walls — in the middle of a city where a fate like ours was a lucky one. Still: “I wanted it,” I said.

That the card had made it to New Orleans after all those months — that flimsy square of paperboard: where had it been? where had it gone? — seemed to corroborate my faith in the coincidence that had inspired it. Sure, logic told me it was foolish not to accept that a chance meeting could be purely chance. But I couldn’t help feeling a persistent awe at the encounter on Van Brunt. The likelihood of Florence being outside and Marjie and I both poised on the sidewalk in front of her building in the very same instant seemed impossibly small.

Our coincidence had convinced me that I was in the right place, there in New York City, and the corresponding sense of good fortune had carried me through the difficult weeks and months that followed. When my mother texted me, on the September morning when she and my father were first allowed to go home, to say Standing in your bedroom Can see the sky, my distress (the ceiling had collapsed under a hole in the roof) was matched by relief that the room was there at all. I was even aware of how Katrina itself brought a kind of luck: it nullified my post-college existentialism, reminding me of what was so much more important than launching a personal or professional trajectory — friends and family, shelter and food.

So, though I still didn’t have full-time work come October, the decision to stay in New York was an easy, unthinking one. The city had given me something to believe in — luck — at a time when I needed to believe in it. That fall, events that might have seemed ominous to someone unsure of their relationship with the city — or unaffected by Hurricane Katrina — felt oddly incidental to me: one evening, I left a bag of my favorite clothes and journals in a taxi and never got it back; another time, a teenage girl deliberately kicked me down in a Queens subway station, causing me to knock my head on the platform.

That day, two strangers from the R train insisted on taking me to a café nearby to get ice. They told me about the man who’d run after the girl, shouting at her — they’d thought he was my boyfriend — and then called an ambulance to check if I’d had a concussion. Afterward (I was fine), one of the EMTs began copying the address from my Louisiana driver’s license onto an insurance form.

“You can’t send mail there,” I informed her, repeating what I’d read and heard in the news. “They won’t deliver it.”

She asked me for another address, but I didn’t have one: I was about to move out of my sublet, but wasn’t yet sure where to. “Forget it,” she said, ripping the paper. “It’s fine.”

“What are you doing?” the second paramedic asked.

“She’s from Louisiana,” the first replied, and I don’t know why, but it was then, hearing a stranger pronounce “Louisiana” with such emphatic gravity, that I felt the dizzying sense of loss I’d not yet allowed myself to feel. The episode in the ambulance had seemed to be another link in the chain of my good fortune, but her tone briefly laid it bare: the New Orleans I’d known was gone; I’d never again be able to claim the place where I’d grown up in a way that was easy or uncomplicated.

For an instant, I felt sure I’d never see the postcard from Red Hook again, either. But the kind of faith that had persuaded me, until then, that there was still a chance of its turning up — the same stupid faith that had led me to mail it in the first place; the same childish belief in magic that had inspired me to write it and, later, to perceive the fallout of Katrina as a form of good luck — that kind of faith is not easily lost. Like the postcard, it can disappear for a few months, or even a few years, and you can try to throw it away, but it’s there in the way we return and rebuild, and even in the way we forget. It’s a form of denial, yes — denial of danger, of gravity, of grief — but it’s a denial as natural as the refusal to believe that a chance meeting can be only chance. It’s called hope.

— Helen Rubinstein

Helen Rubinstein’s essays and fiction have appeared in Ninth Letter, The New York Times, Electric Literature’s Outlet, and elsewhere. She teaches writing in Brooklyn and is working on a book.