exhibition

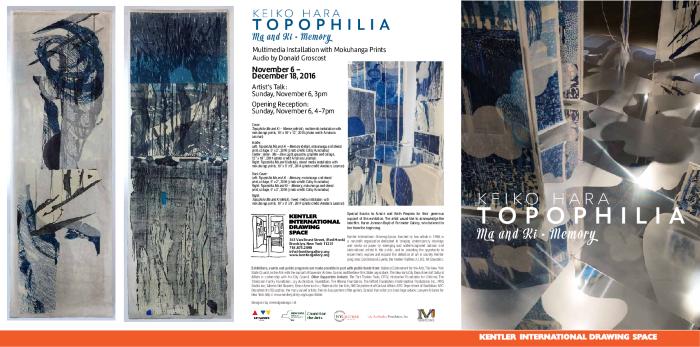

Keiko Hara, Topophilia Ma and Ki - Memory

Date

November 6 – December 18, 2016Opening Reception

November 6, 2016Essay By

Lilly Weiexhibition Images

Click to Enlarge.

Topophilia Ma and Ki – Memory (detail), multimedia installation with mokuhanga prints, 10’ x 10’ x 12’, 2015 (photo credit: Amahara Leaman)

Keiko Hara, Verse Ma - Blue Light, 2014, Gouache, sumi ink, graphite pastel and collage, 12 in X 18 in.

No longer available

Keiko Hara, Verse Ma - Floating Memory, 2015, Gouache, sumi ink, graphite pastel and collage, 12 in X 18 in.

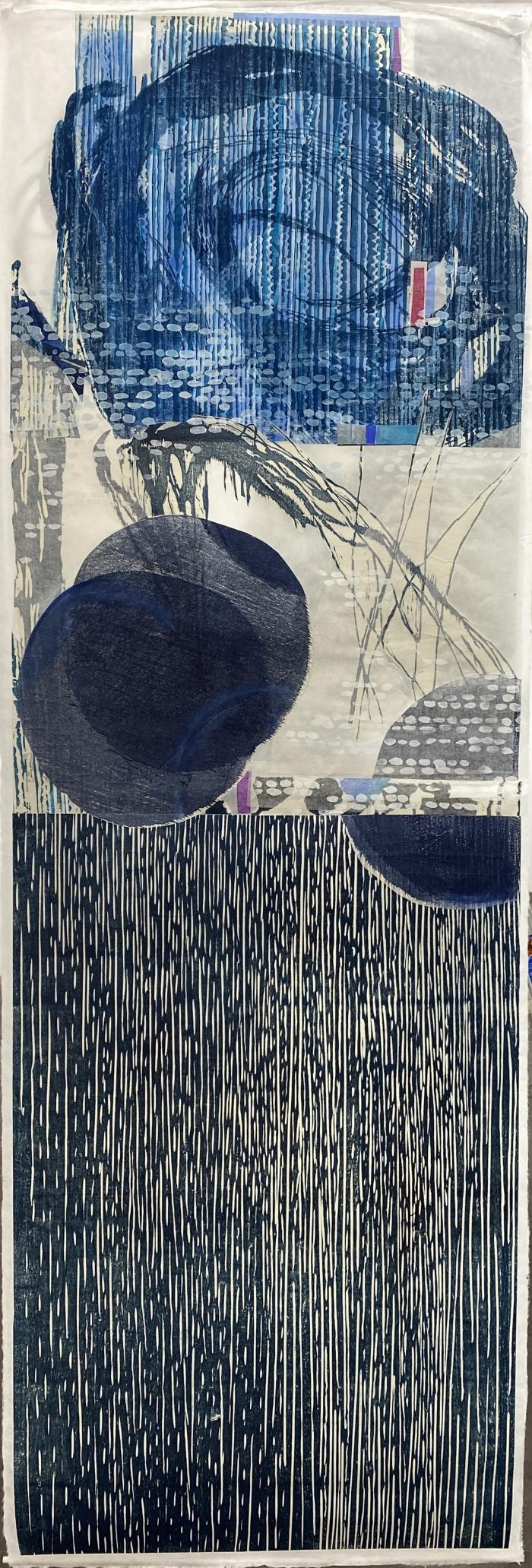

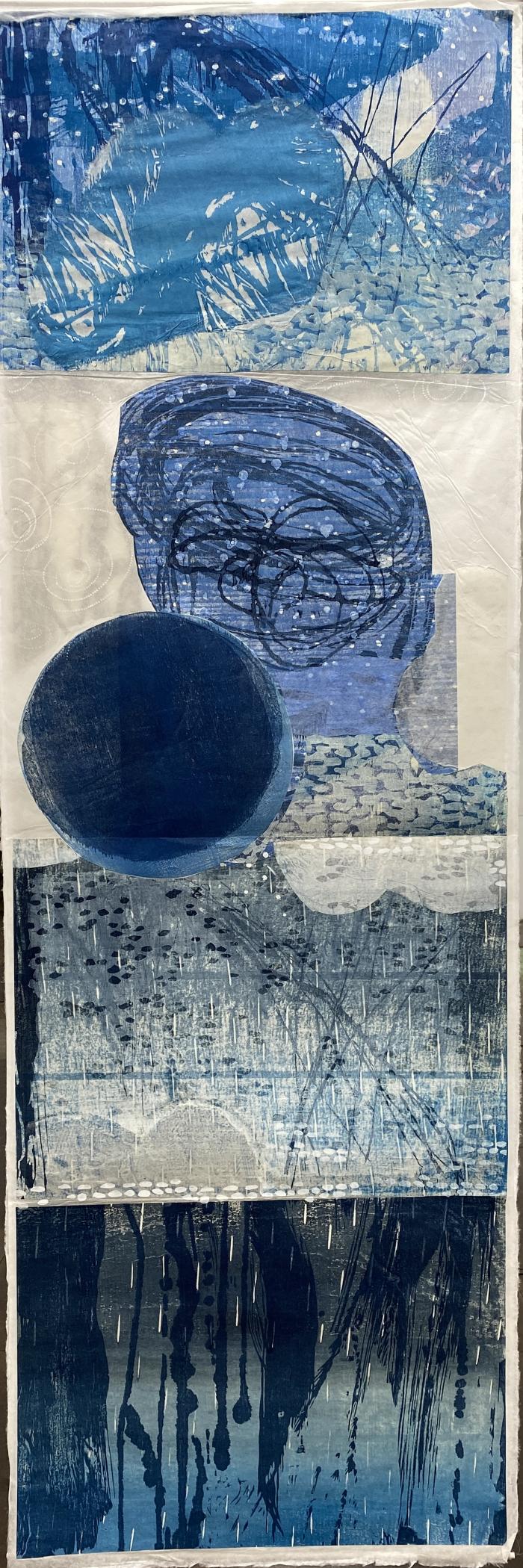

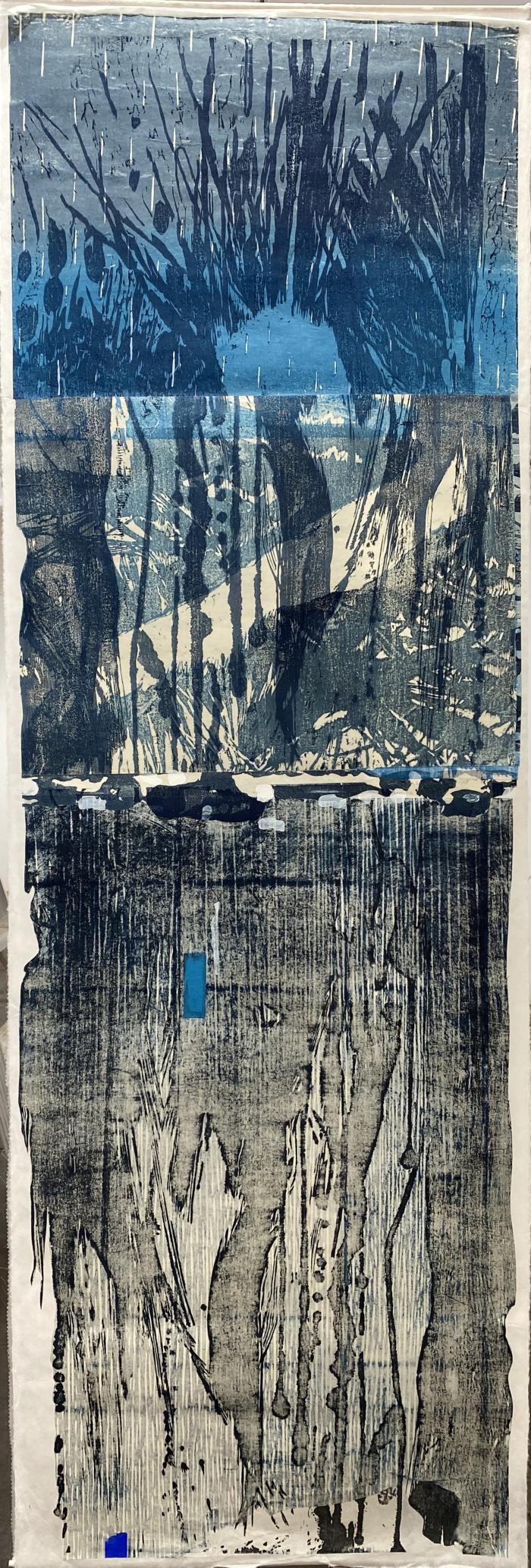

Keiko Hara, Topophilia Ma and Ki - Memory, 2016, Mokuhanga, stencil and collage on washi scroll (2 sides), 72 in X 24 in.

No longer available

Keiko Hara, Topophilia Ma and Ki - Memory, 2016, Mokuhanga, stencil and collage on washi scroll (2 sides), 72 in X 24 in.

No longer available

Keiko Hara, Topophilia Ma and Ki - Memory, 2016, Mokuhanga, stencil and collage on washi scroll (2 sides), 72 in X 24 in.

No longer available

Press and Promotion

About the exhibition

Keiko Hara

Topophilia Ma and Ki – Memory

Multimedia Installation with Mokuhanga Prints

Audio by Donald Groscost

November 6 - December 18, 2016

In Silence, with Sound, Recurrent

Topophilia Ma and Ki—Memory is the latest incarnation of Keiko Hara’s ongoing series of mixed-media installations of that name (from the Greek, defined as a profound sense and love of place), based on a theme that has engrossed her for the past three decades. This edition is dedicated to the memory of her parents and the end of her family’s name in Japan, a name that had existed for more than 350 years, the artist said. Broadening the sense of pathos beyond the personal, it also commemorates the calamitous earthquake and tsunami of 2011 that struck the Tōhoku region in the northwest of Japan, the worst ever recorded in the country’s history, causing the meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactors, a disaster of unprecedented magnitude. The death toll was immense, claiming nearly 16,000, with 2,500 persons still missing, numbers that Hara wants us to remember not as a bundled statistic, an abstract aggregate, but as what they truly are—the grievous loss of human lives, each with his or her own story. After visiting the area in sorrowful tribute to those lost, Hara began this extremely poignant project, perhaps the most immersive she has conceived to date, creating a water-themed fantasia that occupies the entire gallery. As a coincidence, the venue for the exhibition, the Kentler International Drawing Center, is located in Red Hook near New York Bay and suffered its own storm damages and flooding in the wake of Hurricane Sandy in 2012 as it wreaked especial havoc throughout the neighborhood.

Hara, of Japanese ancestry, was born in North Korea, raised in Japan, then came to the United States in 1971, where she completed her art studies, earning her MFA in printmaking at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan in 1976. She taught for many years, her longest tenure at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington. While her practice is multidisciplinary, she is particularly known as a master printmaker and an authority on mokuhanga (Japanese woodblock printing), which has a venerable history and was the primary technique used in the production of ukiyo-e (pictures of the floating world), the popular genre of prints that flourished in 17th–19th century Japan, depicting the demimonde of Edo (Tokyo) and its delights.

Topophilia Ma and Ki—Memory, places far greater emphasis on light than previous work and is more assured than ever in its deft melding and balancing of watercolor with woodblock printing. Constructed from a variety of materials, Hara’s work is characterized by the density of its layering. In her “Topophilia” installations, that density is translated into the three-dimensional, the many elements that comprise her two-dimensional work separated to form a more sculptural, more architectural construct.

Here, Hara overlays in another way. Each of the fifty hanging panels consists of two sheets of semitranslucent washi, a Japanese paper, backed with silk. Each sheet is printed and the viewer can see through it the ghost image of the other side. She used lighter and darker shades of indigo for the most part, her volatile marks and abstract patterns looking as if they had spontaneously erupted: natural phenomena painted by natural processes. Interrupted by streaks of white that seem flung across the surface, the dashes evoke wind-driven splatters of waves, rain, sleet, snow—or of glimmers of light. The images on either side of the paper commingle when illuminated and suspended in space, forming a composite design of indeterminate depth and subtle movement. Accompanied by a system of lights that add brilliance and shadows to the installation—painting them in yet another way—each panel is lighted individually. The sense of sparkle and flux is further abetted by fifty shining, round, multi-lobed aluminum cutouts that cast their own reflections and might be stylized chrysanthemums, a flower that signifies the Japanese imperium, or lotus flowers, emblematic of Buddhism, Hinduism, and more. Hara’s references are wide-ranging, with multiple inferences.

The floor is tiled in reflective aluminum. Sandblasted, it resembles the granularity of that substance, as if it were an expanse of rippled, sunstruck water through which the ground is visible. Solidity, however is subverted, dissolved by its mirrored surface into uncertainty, the ground transformed into a semblance of water and air. The installation as a whole is a spiral, a form frequently found in nature and the cosmos. Suggesting a wave, it is another symbol, one that includes rebirth, recurrence, and renewal in its iconography. The panels are hung at different heights, beginning low but then ascending in a visual and metaphoric crescendo. Leading the viewer through the space in an allegorical journey, the space/time element is enhanced by a sound component that envelops the visual structure, an invisible but potent presence like an aural painting. Conceived by Donald Groscost, a New York–based artist and musician with whom she has collaborated in the past, it is a four-minute loop of sounds both “sampled and created electronically.” He calls it a “palette of sounds” that corresponds acoustically to Hara’s installation and themes, evoking her affirmation of implacable nature in all its contradictions as it sustains and overwhelms us, as we conserve and heedlessly destroy its precious resources.

Hara was raised by the Inland Sea in an area that is not dissimilar to Fukushima and Sendai in landscape. Both regions are on the coast although one is in the south and the other the north. As a child, she was utterly mesmerized by water, gazing at it for long periods of time. The sea is like a blank canvas, Hara observed, and making marks is similar to the play of waves across its surface, endlessly redrawn, the water remembering nothing. Storms fascinated her, with their huge crashing waves, fierce winds, and turbulent skies. It was sheer primal energy, terrible and exhilarating to behold. Curiously, she believed it was safer to be in the water during such tempests so she imagined a miraculous place under the sea, one that would be a sanctuary from violence, between worlds, out of time.

Topophilia Ma and Ki—Memory movingly addresses the inner sense of place that she envisions within each of us. It is a dream space that touches on life and death and their constant cycling, on the sublime and the humble. What she wants to offer is a place of consolation and hope, needed more than ever in these tumultuous, uneasy times. She believes that life is a “spirit woven through space and time” and that “existence is a continual process,” always beginning, a thought that might sustain many of her viewers.

—Lilly Wei

Lilly Wei is a New York-based art critic, art writer, journalist and independent curator whose focus is global contemporary art.